Posted by:

Chris_McMartin

at Wed Apr 24 06:24:51 2013 [ Report Abuse ] [ Email Message ] [ Show All Posts by Chris_McMartin ]

I intended to write an article following up my February piece, “Join or Die.” The editorial generated a wealth of discussion on one forum to which it was posted, but on most of the other forums I received little or no feedback. Initially I thought of compiling the highlights of the discussion and presenting them here, but after further consideration I decided against it. Inevitably I would likely overlook someone’s valuable input or simply miss something which merits attention, possibly as an entirely separate consideration besides what I wish to discuss here. I may have also inadvertently mischaracterized the main thrust of my train of thought, which I hope to further develop in this article. For those interested in reading a lively discussion generated from “Join or Die,” I recommend the Field Herp Forum “Board Line” message thread, “For Discussion—The Future of Herp Organizations,” found at http://www.fieldherpforum.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=20&t=15083.

The focus of this article is to attempt ONE way to model the “herp community” and potentially provide some direction. Keep in mind this is only the author’s perspective and others’ points of view most likely differ, but I hope it is a starting point from which to develop.

If you participate to any extent in the hobby, avocation, or industry revolving around reptiles and amphibians (collectively, “herps”), you’ve almost certainly been peppered with warnings of threats to said hobby/avocation/industry. There are many options for responding to these threats. Are they all helpful? Does it matter to which particular method of response you choose to devote your time, money, and talent? Are there too many organizations within the community, all vying for the same limited pool of time, money, and talent? What, or who, IS the “herp community” anyway?

Defining the “herp community” must necessarily be broad in scope. I wrestled with how best to convey my thoughts on the matter, and figured a picture is worth a thousand words. It may not be the optimum portrayal, but as previously mentioned it may be a useful point of departure.

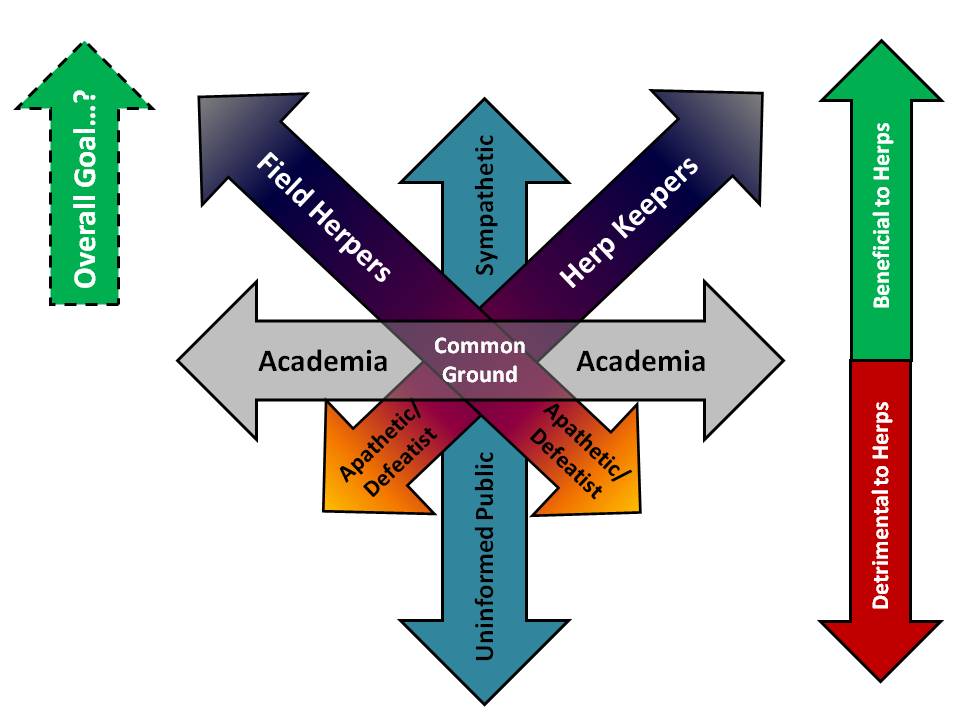

What I perceive as the “herp community” can be loosely described by referencing Figure 1 (below).

The community itself is depicted by overlaying several arrows on top of the “non-herp-oriented public.” The orientation of the individual arrows is important, as I will explain later. The vertical arrow on the right is a general trend—downward orientation on the depiction of the “herp community” translates into states of being (who a person “is” with regard to the “herp community”) I perceive as detrimental to the animals themselves—on an individual-specimen basis and/or to species/ecosystems as a whole. Similarly, upward orientations reflect states of being I see as beneficial to the herps.

The vertical arrow on the left, in the general sense, is something I think everyone can agree on as a concept. That is, the overall goal of the “herp community” should be for the betterment of reptiles and amphibians—which, not coincidentally, will in turn contribute to more ability for interaction from the people who appreciate them. I’ve depicted the goal arrow as a dotted line, and placed a question mark within it, because this will be the most difficult task ahead—specifying exactly what that goal looks like—and it may take on slightly different forms for different groups (hint: a herp society’s “mission statement” might be a good fit).

In the figure, I’ve identified several groups: field herpers (those who seek reptiles and amphibians in the wild), herp keepers (those who maintain specimens domestically, including breeders who sell specimens), the general public, and academia (researchers and so on).

The general public is the foundation of the model, and the largest arrow (though not to scale; there is insufficient space to represent it accurately!). The “detrimental” posture (pointing downward) can best be described as “uninformed citizens;” people who dislike snakes out of innate (or taught) fear, or act out of simple indifference (e.g. not swerving to avoid a turtle on the road, but not necessarily because of malicious intent). I’ve labeled the “favorable” posture as “sympathetic,” by which I mean the public who, while not rushing out to photograph, catch and observe, maintain domestically, or otherwise enjoy reptiles and amphibians on a personal level, are at least sympathetic to the animals’ deserving to be treated equally with other, more “cuddly” creatures. Unfortunately, at this time I feel it is most accurate to depict the majority of the public as “uninformed” (or at least “underinformed”); hence the arrow being longer in the downward direction.

The two primary “herping” factions are depicted as arrows largely pointing in different directions—on purposes. Sometimes these two groups are at loggerheads (ha!) with each other, as their goals sometimes seem conflicting. However, I oriented both arrows upward with respect to the “beneficial to herps” trend. On the other hand, as you can see in the diagram, each group has actors which can be detrimental to the interests of their community and to the herps they love—either on a conscious level or inadvertently. I’ve labeled such folks as “apathetic” (those who say “just leave me alone; I’m going to enjoy herps the way I see fit; laws or no laws”) or “defeatist” (those who say “you can’t fight City Hall; no use trying; let’s just remember the good old days”).

The “academia” arrow was placed horizontally for a carefully-considered reason—to maintain the integrity of their effort. Data and research support knowledge, which in itself should be viewed as neither beneficial nor detrimental (outside the intrinsic perceived benefit of knowledge)—however, what other groups choose to DO with that knowledge can have an effect one way or the other. The horizontal academic arrow therefore reflects impartiality.

In the middle of the diagram is “common ground.” Regardless of the specialized focus of any of the groups depicted, there is a Venn-diagram-like shared area. Some field herpers catch and keep some of what they observe. Some herp keepers like to keep exotics, but go field herping to observe natives. Some academic researchers maintain a collection for fun, or enjoy taking friends to study site. This common ground of shared interest is where time, money, and talent can have the greatest impact.

This description of the “herp community” and its relationship with greater society is by no means a perfect one. However, as previously mentioned, I think it is a workable model from which to proceed.

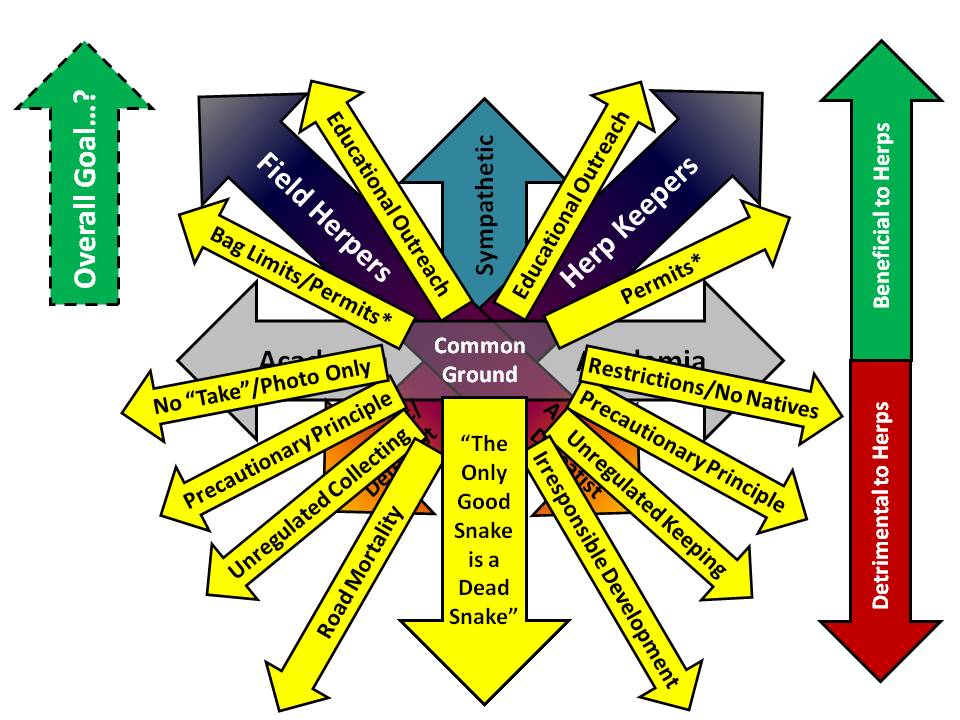

Now that a basic framework of the “herp community” has been established, I will overlay the model with issues and actions affecting the community and reptiles and amphibians in general. Figure 2 (below) shows what I think are some of the bigger issues; it is not an all-inclusive illustration (I wouldn’t have room to show them all!). The size of the arrows corresponds to the relative magnitude of the issue/action; the length of the arrows translates to the relative impact. For the most part, the arrows are aligned left/right with the subset of the “herp community” to which they are most relevant. The orientation of the arrows is my impression of the extent to which each issue/action affects reptiles and amphibians. Of particular importance, the arrows are all the same color. That is because these are all issues which the “herp community” can influence.

The old cliché “The only good snake is a dead snake” dominates the “uninformed” or “underinformed” public arrow. This attitude is pervasive and has, in my opinion, the most severe implications, because it represents willful attacks on reptiles and amphibians. It will be the hardest attitude (with its result of indiscriminately killing snakes) to mitigate.

Road mortality and irresponsible development are two arrows which are not necessarily aligned with any particular subset of the “herp community;” I had to place them where I could, given limited space. Road mortality differs in that some people run over animals maliciously while others may not even realize they’re doing it (especially with smaller species). On the other hand, irresponsible development harms reptiles and amphibians, though not out of any specific intent (I know of no housing tract or golf course built primarily to wipe out reptiles and amphibians; such eradication is merely an unintended consequence).

I have listed the “precautionary principle” twice—on both the field-herping and herp-keeping sides of the model—because it can negatively impact both subsets of the community (and, ultimately, the well-being of reptiles and amphibians). For those unfamiliar, the precautionary principle in a nutshell says in the absence of data to support an action (such as managed collection), the action should be prohibited, “just to be on the safe side.” This is how some states and municipalities justify “hands-off” policies for native species, or restrictions on what (if any) species can be maintained in the home. Focusing narrowly on immediate effects, the precautionary principle may be perceived as helpful, as it could conceivably reduce pressure on native reptile and amphibian populations. However, the long-term effect could be quite the opposite—with citizens unable to interact with reptiles and amphibians, nobody will know or appreciate these animals. Nobody will be overly concerned with the negative consequences of roadkill or development, for they will have no special connection with the animals.

The remaining “detrimental” issues more closely align with the main subgroups of the “herp community” (as depicted in the model). First, let’s look at the issues affecting field herping. The first issue is unregulated collecting. Generally speaking a complete lack of regulation is neither desired from a field-herper’s perspective, nor is it an advisable stance on a scientific basis. Another, perhaps less intuitive, detrimental issue is also a regulatory concept, but one at the other end of the pendulum swing—a “hands-off” mentality, which in some extreme cases even limits the ability to photograph animals in the wild (because getting a good shot may involve “pursuit” of an animal, which can fall under the definition of “take” and therefore be forbidden). Such a hands-off approach may seem agreeable to those who think any interference with wildlife is a bad thing, but again this goes back to the “precautionary principle” with its unintended negative consequences.

The final two detrimental issues fall most closely in the realm of captive maintenance of reptiles and amphibians. Many of us are all too familiar with unreasonable restrictions on numbers and/or types of animals which can be kept domestically. In some cases, “exotics” can be kept, but not native animals; perhaps due to some perceived unsustainable demand for locally-available species. This has the (presumably) unintended consequence of making outlaws of every child whose first experience with nature may be a toad from the backyard. Though perhaps kept in a small container for only a few days, such an experience may well spark a lifetime passion for biology. Conversely, as with field-herping regulations, a complete lack of any restrictions or guidelines for maintaining domestic reptiles and amphibians can also have disastrous results. For example, impulse purchases at poorly-monitored venues (e.g. flea markets) generally don’t end well for individual specimens; it is debatable which is worse—a lingering death from ignorance of an animal’s needs, or being released into the wild (especially where the animal is not native) to fend for itself or frighten people who aren’t “herp friendly.” There is no need to go into detail here about the current problems with breeding populations of non-native species, but they are potentially symptomatic of the larger problem of under-regulation.

If so many issues work in concert to the detriment of reptiles and amphibians (and, as a result, our ability to enjoy them), what can be done to improve their (and the “herp community’s”) lot? A few come to mind; I’m sure others within our community can exercise our collective creativity to devise more.

Our overarching goal should be the betterment of reptiles’ and amphibians’ predicament in the world. However, our sphere of influence is PEOPLE. It’s naïve to tell ourselves “only the herps matter; I don’t concern myself with the people involved.” We can wish or hope for populations to improve in health, but they would get on just fine if we totally left them alone. Unfortunately, mankind has a long history of NOT leaving the natural world alone—nor should we necessarily be expected to. However, we CAN manage our actions to minimize negative impacts.

Who should we be looking to influence to manage these actions? Not every field herper wants to keep herps. Not every herp keeper wants to field herp. We need to influence the public. The goal isn’t to make them “snake lovers” necessarily, but to make them “sympathetic.” More importantly, “the public” is largely where lawmakers originate—there are precious few amateur herpetologists holding elected office.

The single biggest action we as a community can take, regardless of whether we primarily field-herp or keep reptiles and/or amphibians domestically, is to EDUCATE. Field herpers can do this by publicizing their efforts in the field of “citizen science.” Many Federal, state, and local agencies are forming partnerships with organizations such as the North American Field Herping Association (NAFHA) to collect data on native species, especially where available in-house personnel and resources are lacking. Another way is to provide training on local species to police, fire fighters, and other emergency responders as well as park rangers. Keepers can obviously showcase their animals in educational displays wherever and whenever they can do so responsibly. Community events organizers are often very interested in hosting such displays. Don’t expect these people to know you exist—make your willingness to contribute known, either on an individual basis or as part of a local herp organization.

My second recommendation as an action the “herp community” can take is to get involved in regulation of our interests. You’ll notice I included an asterisk in these arrows—allow me to explain. Regulations may seem like a negative, but the fact of the matter is that if WE don’t get involved, the regulations will still be imposed by someone ELSE (often taking the form of additional restrictions). It is difficult to make the case that bag limits are not needed, but the other side of the coin is that it SHOULD be difficult to impose “zero” bag limits—but with the “precautionary principle” mentality in vogue, that is sometimes what happens, because lawmakers simply do not have solid data with which to make their decisions. Similarly, would a permitting process for field herping and/or keeping reptiles and amphibians necessarily be a bad thing?

That last sentence should really get your attention. You’ll notice I didn’t say WHO should be the overseer of a permitting process. I strongly advocate getting out in front of this concept, as a community of reptile and amphibian enthusiasts, by organizing into a coherent group and SELF-regulating. On at least one herp-related audio program this has already been proposed, using the SCUBA community as a model—there are essentially no laws pertaining to SCUBA diving, yet it is a safe pastime enjoyed by hundreds of thousands of people worldwide, because the community has self-imposed restrictions and guidelines. Proof of training, for example in the form of a certification card from a private organization (e.g. the Professional Association of Diving Instructors, or PADI), is almost universally required in order to rent equipment, get tanks filled, and so on.

Similarly, it should be easy to conceive of a process by which prospective reptile and amphibian hobbyists could be certified by a national-level organization, with a hierarchy of certified instructors, to keep various species based on level of difficulty. Breeders and pet shops would participate by pledging to refuse to sell animals or supplies to anyone not able to produced proof of training, and perhaps offering a discount to people trained to a higher level. On the field-herping side, certification could be a means to gain access to additional herping areas (government lands heretofore off-limits) and give private landowners an extra measure of confidence toward people they permit on their property.

This of course would be a complex task, but with the advent of several national-level organizations the groundwork has potentially already been laid. The momentum merely needs to continue—once we can reach consensus on which direction the organizations need to proceed.

I hope this article has provided food for thought; while I realize the proposals contained herein are not final products, I do hope they provide material to further discussion.

-----

Chris McMartin

www.mcmartinville.com

[ Reply To This Message ] [ Subscribe to this Thread ] [ Hide Replies ]

Finding Direction in the Herp Community - Chris_McMartin, Wed Apr 24 06:24:51 2013 Finding Direction in the Herp Community - Chris_McMartin, Wed Apr 24 06:24:51 2013

|